The Somali-Kenyan Issue

When talking about the Horn of Africa, it is not enough to tell the history of that region in order to learn the current state of affairs, but one has to arrive at the facts hidden from all but the peoples of that region who not only make it clear that they suffer local and regional misunderstanding, but also presume it’s difficult to resolve misunderstandings or else mankind would have been capable of avoiding historic disasters, or so the legend goes.

The Somali-Kenyan issue is actually more complicated than it seems, especially for the Gulf reader who still picks news about the Horn of Africa from local or foreign newspapers or from reports and references that reflect not the interests and vision of the Horn of Africa peoples, but rather the interests and vision of the countries of those writing these reports and references. Unfortunately, those oriented reports impacted the vision of the Gulf political decision-maker towards the Horn of Africa.

Nairobi’s talk about its intention to build a border wall between Kenya and Somalia denotes fear of witnessing political instability on its own soil in one way or another. Nairobi considers that the Somali territory of NFD, which it occupies, will never cease opposition to the Kenyan government, nor will it be harmed by the construction of the forthcoming border wall. The majority of the territory’s residents are Somalis who wish to return to their mother country “Somalia”. They do not differ from their counterparts inhabiting mother Somalia or even those living in the Ogaden Somali region occupied by Ethiopia as they speak one language and belong to the same clan; all Somalis are Muslims and commonly affiliated to the mystic doctrine. Even dialect differences are not consistent with the artificial boundaries imposed either by Nairobi or Addis Ababa. This has been perceived and exploited by terrorist organizations such as Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen by recruiting young Somalis in those militias which have become increasingly active in the Horn of Africa after announcing the establishment of the Islamic State-affiliated East African Front. Consequently, I do not think that Nairobi will be safe from inevitable future terrorist attacks after the construction of the prospective Wall on the one hand. On the other hand, I cannot fancy that Nairobi’s support for Jubaland and Ahmed Madobe, known in East Africa as (man of Kenya in Somalia) will stop even after building the Border Wall.

Kenya has witnessed terrorist operations, starting from the U.S. Embassy bombing in 1998, through Westgate in 2013, and Garissa 2015, and Dusit D2, 2019. Kenya has no choice but to be linked to past, present, and future incidents in Somalia in particular, which could be traced back to the year 1963.

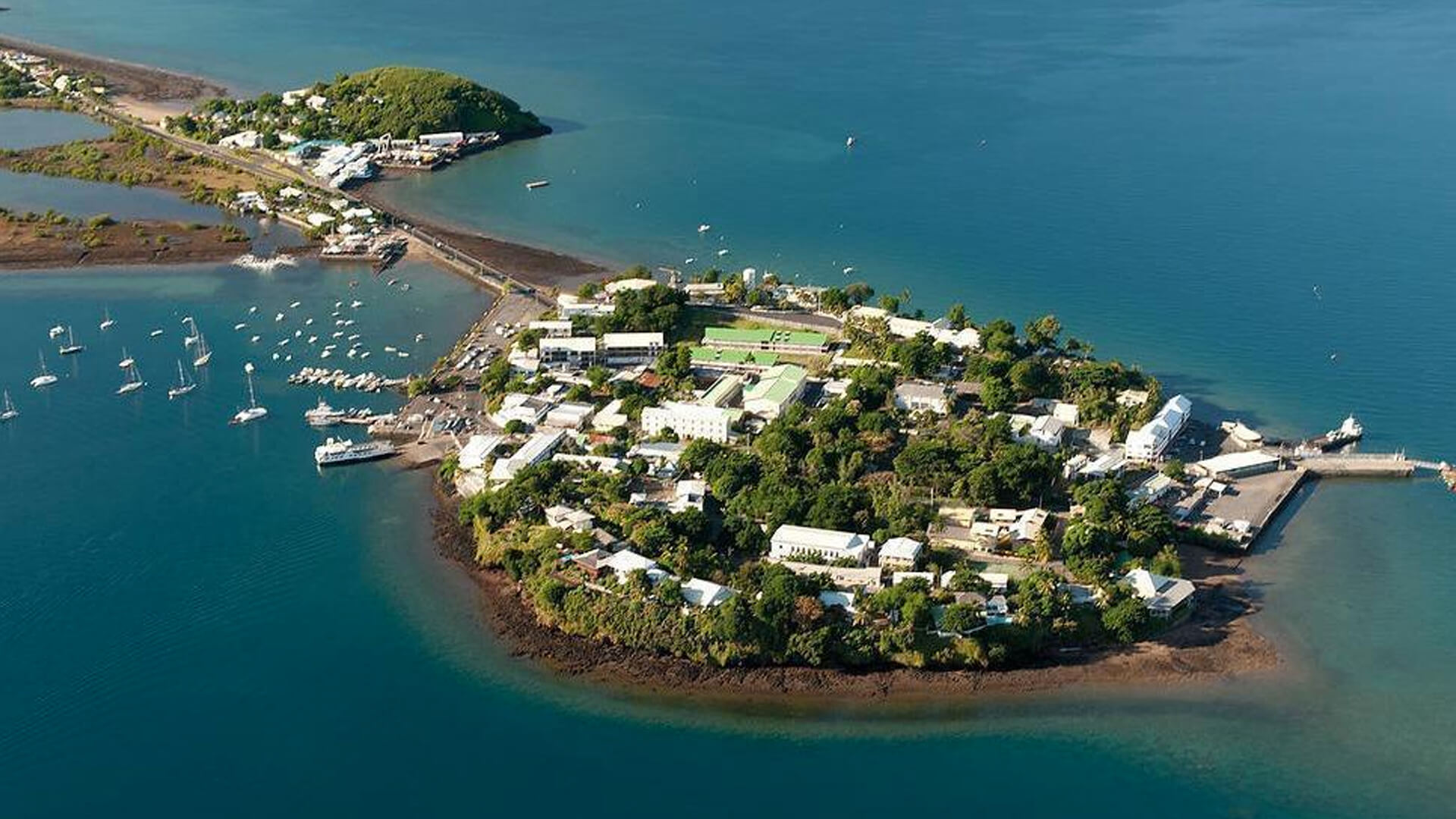

Since the colonization annexed the Somali territory of NFD to Kenya, Nairobi has almost been the most unstable capital in East Africa which in turn led to the complication of its domestic issues. Under the pretext of protecting its national security, Nairobi tried to enter the Somali territories with the UN approval and within the forces of African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) to eliminate the Somali al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen. Kenya believes that the construction of a 100 km buffer zone inside the Somali territory bordering Kenya will help it exploit the region’s economic resources and take full control of the Port of Kismayo, which is considered a supply base and a communications and maritime surveillance center for al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen, besides opening of a secure sea lane for targeting al-Shabaab. The Port of Kismayo is the lifeblood for al-Shabaab and provides Kenya with a link outside Somalia, which is the direct strategic goal of the Kenyan military intervention under AMISOM. But why couldn’t Nairobi eliminate al-Shabaab that represents the greatest threat to its national security?

The Kenyan elite believes that Al-Shabaab outperforms the AMISOM in terms of intelligence due to its close connections with the people in areas under its control, its total immersion in local culture and dialects, in addition to acquaintance with the region’s minute geographic terrain, a thing that advantaged them with flexibility of movement, predictability and planning.

Personally, I agree with the Kenyan elite regarding their previous opinion that the AMISOM functions independently from the security, intelligence and military coordination of the international powers. I add that the international powers wish that al-Shabaab and its arms retain half-power in order to use them as a leverage in the future, and thus will not allow a negotiated solution with them, a solution that had been promoted by some international media platforms, commenting: “Nairobi should lower expectations of defeating al-Shabaab and should instead weaken their military capacity and seek a negotiated solution.”

The question remains here: What if the international powers were cooperating with the AMISOM? Would al-Shabaab require such a long time to defeat and eliminate?

I think that Nairobi is about to witness important developments because the military and intelligence cooperation with Ankara is likely to be strengthened, which will support the security agreement the two sides signed in 2016. I do not believe this security cooperation will be isolated from the US military command in Africa (AFRICOM) which carefully observes developments on the ground. The Kenyan-Somali border will either witness cooperation that reminds us of Operation Linda Nchi, which is a joint Somali-Kenyan operation meaning “protecting the country”, or tensions especially in border areas, as the current incidents on the maritime boundaries and oil fields, something that will bring to minds the International Court of Justice intervention to settle border disputes in 2012. This may lead some organizations such as the East African Front to resume activity, which would destabilize both the Kenyan and Somali scenes. Nairobi will utilize the recent terrorist attack to convince the Kenyan public opinion of the necessity to expedite construction of the Kenyan-Somali Border Wall irrespective of its cost especially that it faced much criticism over the construction costs due to the lack of a clear budget plan for the project cost estimated at $ 260 million.

Addis Ababa and Djibouti are likely to support the Kenyan project to be built on the Somali border, especially since there is a common interest among countries neighboring Somalia and which is certainly not in favor of Mogadishu. In the next time, the Kenyan-Ethiopian relations will witness positive development through Ethiopia’s keenness to persuade Nairobi to try to curb the growing Kenyan opposition led by former Kenyan Prime Minister “Raila Odinga” which destabilizes the political situation in the country. This is despite Addis Ababa and Ethiopian politicians’ being assured that no future Kenyan president will fulfill the Somali dream of retrieving the NFD territory. Consequently, Addis Ababa’s cooperation with Kenya comes in the context of preventing further aggravation of the situation in Nairobi and out of keenness to complete the Renaissance Dam apart from tensions, whether in the Ethiopian interior or in the basin states that eagerly await the completion of the Renaissance Dam which is linked to its development. Between this and that, Nairobi finds itself in a race against time, especially that it has been classified among the most important African capitals attracting business because of the advanced technology that enabled Nairobi to surpass the entire of East Africa and compete with South Africa. On the other hand, Kenya is preparing to be the main station in a 5,000 km railway network that Ethiopia intends to inaugurate in 2020 with links to Kenya, Sudan and South Sudan. With these positive developments, Nairobi finds itself divided between accomplishing tasks and challenges, and eliminating terrorist organizations that plague the nation and citizens and impede development.

No doubt, Kenya is an important country in the international strategy, and here, we must highlight the American viewpoint concerning Kenya. In conferences that I have been invited to, I often begin my speech about Kenya by a statement by the late journalist Mohamed Hassanein Heikal: “Major powers do not easily shift their strategies, for these strategies are not the result of whims, not established by the rise or collapse of a regime, neither they are impacted by a change of presidents. Strategies teach us that goals could be approached directly or indirectly with them remaining clear in both cases, even though if fluctuations occur”.

Washington has recognized the significance of Kenya in the US strategy since its independence in 1963. This resulted in strengthening diplomatic ties and military cooperation, which accumulated in choosing Nairobi as a center for security operations and intelligence partnership. Recently, Washington announced the Power Africa Initiative that aims to add more than 10 thousands megawatt of clean power generation capacity. That initiative included the largest wind power generation projects in Africa, called “Apollo Kenya that was opened recently, and which indicates the US Congress approval to extend The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA)” which strengthens the Afro-American economic partnership up to 2025, which will in turn provides the necessary guarantees for long-term US investments. It is worth noting that since January 2019, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have become eligible to receive the benefits of AGOA, led by Kenya, which is the most technologically advanced country in East Africa, a thing that made it a haven for younger generation in Africa. Faced with these developments, Nairobi’s ambition to develop its infrastructure increased which is part of the Vision 2030 development program that seemed in line with its accelerating technological development. Nairobi found its way in The U.S.-Africa Business Forum held in New York in 2016 after the forum announced payment of nine billion dollars to support trade in Africa. Kenya also found opportunity in the presence of the American company “Bechtel”, especially that it has more than seventy years of experience building and managing infrastructure projects in Africa. Bechtel Company, one of the most prominent international companies in the field of engineering and construction intended to construct one of the most important projects in East Africa, which is a highway that will link the capital Nairobi to the sea port of Mombasa. The project was funded by US export credit agencies such as The Export–Import Bank of the United States and The Overseas Private Investment Corporation which is the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation that mobilizes private capital to help find solutions to development challenges. Before initiating the project, it is reported that Nairobi sought the expertise of “PwC”, one of the major multinational professional services networks that conducted a commercial and technical feasibility study of the Nairobi Mombasa Highway. It is worth noting that this network had predicted in 2017 that the international drone market will reach 127 billion dollars by 2020. It also drafted the “E7” symbol to describe emerging economies expected to arise by the year 2050.

But the obstacle that faced Bechtel is Nairobi’s rejection of its implementation model and its insistence on another. To clarify the disagreement between the two sides, Bechtel confirms that the alternative partnership between the public and private sectors adopted by Kenya will cost five times the amount of fifteen billion dollars and will take a longer time. At a time when Nairobi demands preliminary financing from Bechtel, asking to meet its demands through levies, Bechtel believes that this will cost Kenyan taxpayers five billion dollars over two and a half decades. Bechtel warned Nairobi if it chooses the other way, then it will be in the negative cash flow area, and this will entail paying five billion dollars annually over twenty five years.

Kenyan elites realize that this US-subsidized project came as competitor to China which carried out the most important infrastructure projects in Kenya. What’s more, scholarly sessions on international relations indicate that the Nairobi-Mombasa Highway was originally allocated for a Chinese company carrying out global civil engineering projects, but Beijing recently caused political controversy in Nairobi because of its monopoly of high positions in the Kenyan railways for the benefit of Chinese employees. This gave Washington the opportunity to win the project that will achieve revenues, jobs and opportunities for growth at home and abroad, especially since the Kenyan public opinion believes that the returns of this project will be twice as its cost.

What currently complicates the Somali-Kenya issue and promises further complication in the long term is the recent dispute over maritime border with its oil resources. This dispute will be resolved at the International Court of Justice, but when and how?

Perhaps Washington’s recent announcement (3-10-2019) of reopening its embassy in Mogadishu after three decades answers our previous question as the reopening of the American embassy in Mogadishu is but an adjustment of regional and international balances. The current happenings in the Horn of Africa do not require Washington to exercise its usual proxy role with some parties, for there are some that must be confronted and curtailed, such as China.

In my opinion, Washington had not actually left Somalia and the reopening of its embassy in Mogadishu after decades is only an expedition of a coming process to handle the Kenyan-Somali maritime border issue on the one hand, and tightening control over the New Sudan on the other via assigning roles according to its strategic vision. Washington understands that the maritime border rich with oil fields and disputed between Nairobi and Mogadishu is an inherent right of Somalia, and the International Tribunal’s decision, however late, will be in favor of Mogadishu. But Washington is persuaded by Nairobi’s provocation and procrastination for Mogadishu in this issue because it leaves the door open for a US initiative to resolve the dispute. On the other hand, Nairobi is confident about Washington’s support but that doesn’t mean the latter will deny the right of Mogadishu. It’s likely that Washington will devise an equal deal with both sides, that Somalia may take part of its right in return for resolving some issues and provision of support to the government of President Mohamed Farmajo in order to empower him internally. Washington hopes that Somalia will be satisfied in the medium term at least or otherwise the latter will no longer support the Eritrean-Ethiopian reconciliation. Consequently, Washington will save substantial loss that might exceed the one underwent in Somalia during the 1990’s which the US media avoids mentioning, let alone repeating it. Washington is unwilling to see a destabilized Somalia, being its gateway to the African oil which is considered superior to its Gulf counterpart. Moreover, Washington cannot lose the Eritrean-Ethiopian reconciliation issue it began planning decades ago, along with the re-shaping of the New Sudan which has to normalize relations if it wishes to rise and develop.

Concerning the Gulf States, I believe the current Kenyan-Somali dispute will be affected by the policy of the conflicting Gulf axes and will be further complicated in the short and medium term. That dispute will be fueled by political parties and their representatives who found outlet in the Gulf resources and the Gulf States on their part will divide between Nairobi and Mogadishu. Somalia’s recourse to the International Court of Justice over the disputed maritime border with Kenya will definitely be in its favor, but that won’t prevent continual unrest and skirmishes backed by Gulf resources at that border zone and around. That scenario is dependent on the goals set forth by Washington in the first phase of its official return to Somalia.

Dr. Amina Alarimi,

UAE Researcher in African affairs

27 APRIL 2020